Recently I was with a group of people and we were talking about what was going on in our lives and the topic turned to one of the girls there who is leaving her job soon. “I know it may be bad,” she relayed, “but I’m really giving it my all now. I want them to miss me when I’m gone. I want them to be sad to see me go, and not think ‘Oh, she was leaving, that’s why she was slacking those last few months.'”

Other people in the room chimed in saying they felt the same way. It was quickly clear the desire to be hard to replace seems to be almost innate. Except in me.

For a long time now, I’ve been trying to make myself replaceable. And it’s just been the last few months that I’ve really realized how this mindset has sunk in to most every area of my life.

I create “truck binders” for projects I work on so that if I were run over by a truck, someone could use the binder to carry forward. I delegate tasks and responsibilities to teams and train others how to do my job in my absence. I plan ahead and I make notes about what I do and how I do it. And I’ve realized, I keep people at bay in my life, and I try to get them close to other people who could fill my role when I leave.

When I left for college, I didn’t want to be replaceable, because I wanted to stay in my hometown. But because I left, I wanted to see my people taken care of. I was happy for her when my best friend began to be good friends with another girl who is her best friend to this day. I was glad that someone could fill the hole I left in the day to day life of my friend. I’ve been tentative to sign art pieces that I make for people as gifts, because I want them to be able to enjoy the art piece regardless of what happens to me. I don’t want them to have to remember me with each glance at it if they don’t want to. (I know this is poor logic, and not healthy, but it’s the truth.)

In my self-realization that I do this, this is what I’ve found.

***

I mentioned in my “write your own eulogy” post that I always thought I would die young. As early as I can remember I just assumed this to be true. I told this to my friend recently and she said, “see… that’s why I’m scared to have kids. How do you know that your toddler is thinking about death? That scares the crap out of me.”

And really, she’s right. How would anyone have known? I never bothered to mention it. I just thought it was a given. I was extremely happy and adventurous and risk-taking. I was well socialized. I connected well with people of all ages. But I’ve always thought my time was limited.

The only thing I can think of that I believe made me assume my life would be short was this: My mom always used to tell us stories about her and her brothers as they were growing up. One of my uncles was older than her and one younger. But the thing was, in the story I had two uncles, but in life I only had one. Her younger brother had died before I was born. I only knew him through the stories.

And somehow I think that my little mind drew a lot of similarities between myself and my Uncle Randy. We were both the youngest of 3 kids. We both had allergies. We both got manipulated by older siblings, but still loved them. Just typical stuff. But somehow I believed that my fate would be like his – I thought my life would be short. So I lived that way.

When I was in 6th grade I started to have medical problems. They couldn’t figure out what was wrong but I underwent test after test, with no results giving an answer. I had my blood drawn weekly for a while for these. I saw specialists. I missed lots of school. I was just waiting for what I knew would eventually be a fatal diagnosis. I could manage life 5 or 6 days out of 7, but I missed at least one day of school a week. But on my good days I would play hard, laugh hard, study hard, and be who I wanted to be. I knew time was short.

And then, when my medical problems were still going on, but were becoming less demanding, and almost seemed like they were fading, my older sister died suddenly.

I felt like the universe had gotten confused. She was supposed to live. My brother too. They were supposed to live long, full lives. They were both so accomplished. So smart. Smarter and better than me, I always thought. It was supposed to be me. I had always known. It was supposed to be me who died young. I was supposed to live an entertaining full, short, life that she could tell stories about to her children. It wasn’t supposed to be her.

I was ready for the fatal diagnosis. I wasn’t ready for the fatal call of someone else’s death, though. Cancer, some weird disease, “You have 3 days to live,” I could’ve handled. But watching the life go out of my brilliant, vibrant, feisty, 21-year-old sister who had so much promise for the world and for the people around her — that ruined everything I thought I knew about how to live well and die well.

This death was not like the movies, with time to prepare and goodbyes properly said. It was her birthday 3 days before. We didn’t get to say goodbye. She didn’t get to graduate college one month later like she was ready to. She didn’t get to celebrate her one year wedding anniversary that summer on the cruise they had already bought. There were no tears of parting on her part. It just ended. Like a book that just stops a quarter of the way in, leaving you hanging, knowing there was supposed to be more.

My poetic notions of short life well lived were smashed. This was not like that. This was a life-halting, heart-breaking, “WHAT AM I SUPPOSED TO F***ING DO NOW!?!?” chapter. It was not poetic. It was horrendous.

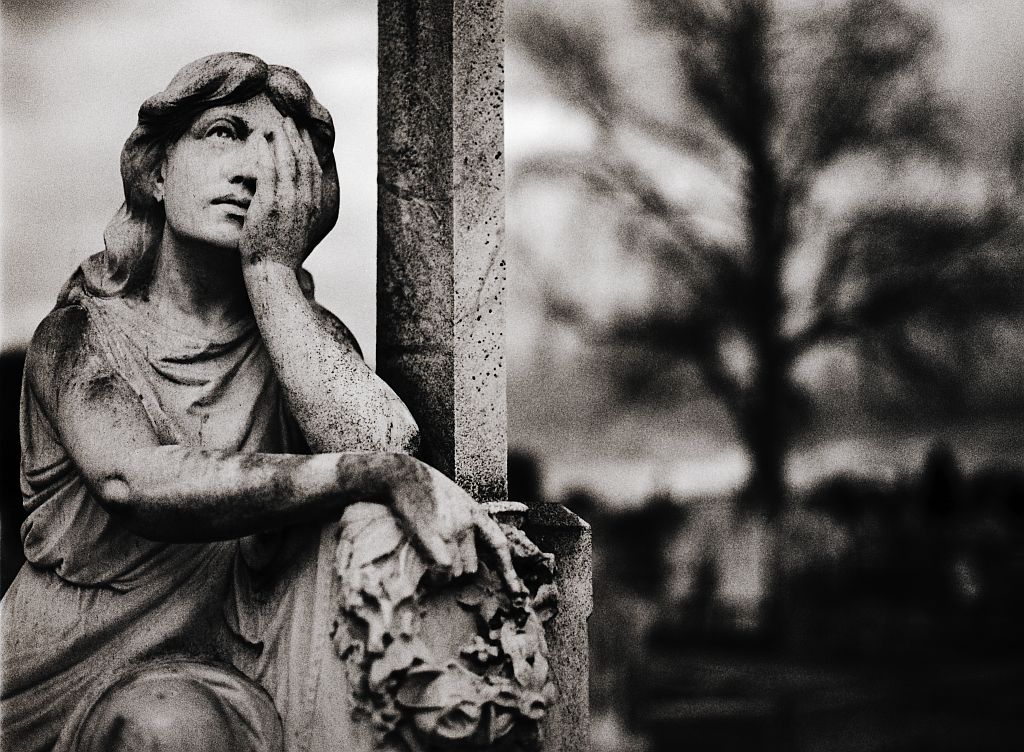

photo credit: mugley via photopin cc

photo credit: mugley via photopin cc

And what had once been a decision to live fully so that I’d soak up all opportunity and so that people could remember me in their stories they told, turned to a desire to minimize collateral damage. I know the pain and ache of someone dying. And I, still subconsciously believing I would die young, was determined to lessen that pain for others as much as possible.

I wanted to be replaceable. I wanted to be able to die and have everything go on without me as smoothly as possible.

I wanted to prepare people for my death — living like a cancer patient without the diagnosis. I wanted people to know how I loved them, cared for them, and that they didn’t really need me. That there were others who could fill my slot in the program of their life.

The first time I talked about “when I die…” to my friend Kate, we were roommates in college. I don’t even know what I said, but probably something flippant like “when I die, I want to have “Damn, it feels good to be a gangsta” on my tombstone. I didn’t know it then (this is just how I talk and think), but she got really angry with me for thinking about death, and talking about it so frankly.

A couple of years later, I had just attended yet another funeral for someone I respected, and I wrote an email to Kate. I told her if I died I wanted her to speak at my funeral, and there were certain things I wanted her to mention: One, namely, is one time that I had the best parallel parking job in the world, on the first try, in golden gate park in San Francisco, and we took a picture that she made me promise I wouldn’t use to brag. I asked her to show said bragging picture, because hey, I’d be dead.

It was in her gracious response that she’d let me in on her reaction to my candor about death. She understands now that it’s part of how I live, but I had never known before that it had angered her and made her sad when I brought it up the first time. Which is understandable. There I was, getting to be great friends with someone, and simultaneously trying to keep a distance, to prepare her for life without me, to make myself replaceable. I believe I may well live a long life now. But I’m still scared of hurting people. I’m scared of leaving a wake of pain should the unexpected happen.

But the thing is, I’m not replaceable. I work hard to make sure I am replaceable in my jobs and roles in life. Because those things you can be replaced in. But I cannot be replaced as a person. Nobody can. I’ve believed that about others, but I thought I could be the exception if I tried hard enough.

I’ve had other people who have stepped in and acted as big sisters for me. But nobody will ever be Julie. And the fact is, if her death had happened like the movies, and we’d had our time for goodbyes, it wouldn’t have made it hurt less. It wouldn’t have lessened the loss. She would still be gone, and still be irreplaceable.

Positions are replaceable. People are not.

So I am working on trying to let myself see this and embrace it in the ways I relate to the people in my life. Because I’ve realized in my efforts to minimize pain for people at my potential leaving, I’m actually stunting the joy of relationships for myself and for them.

I want to step into the fullness of who I am and embrace the value of that woman. And as much as I don’t want people to bear the hurt of loss that I so well know, it’s a lie to go on believing that I can prevent that. Loss and pain are certainties in life. I’d like to focus from now on at caring, loving, giving, and being the kind of friend that I would never want to see leave my own life.

And it’s OK if you miss me when I’m gone.

Joanna O’Hanlon is an adventurer and storyteller. She tries to be honest about the ugly and hard parts of life, and the beautiful parts too. This blog is one of the places she shares her thoughts and stories.

Other places are

instagram: @jrolicious twitter: @jrohanlon