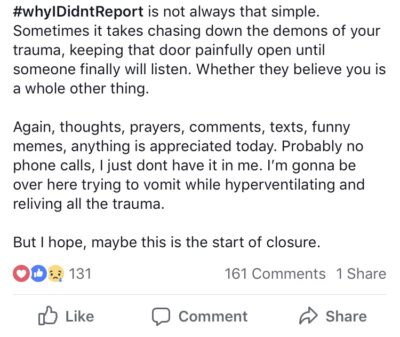

A month ago I shared a post on social media that read:

Some of you have asked how I am after this. About how I feel about how the meeting went. This is how I am. This is how I feel:

Lighter

Sadder

Lighter than I’ve been in since childhood.

Sadder than I expected I would need to be again.

The sadness is the type of sadness that comes at the end. The heavy, warm sadness of acceptance that covers your cold bones with a blanket of truth that you didn’t deserve this, that you weren’t meant to hold this. It is warm. It is surreal. It is anticlimactic. It is the end.

The fight is over. You don’t have to struggle anymore. It’s not that you’re giving up. It’s that there’s nothing left to fight with, to fight against.

* * * * *

It is the sadness of a captive released from the internment camp.

The freedom seems to demand rejoicing, but how can you jump for joy when you are carrying the heavy weight of the past years with you? When you have to swallow that you were never meant to be imprisoned. That you should not have had to endure the pain, the anguish.

That you survived is a consolation, but it doesn’t heal the wound, doesn’t erase the pain, doesn’t take back the years taken, the deeds done, or the memories burned into your being that you cannot shake.

It does not make up for the fact that this is not how it was supposed to be. This is not how it should be. But this is how it is. And at least you’re free now.

Did you know Holocaust survivors are more prone to commit suicide than other people, especially as they age (contrary to a now-disproved theory from the 1900s)? Some reports say about 24% of the survivors have committed/do commit suicide.

Almost a quarter of them. One quarter ‘survived’ but at some point just can’t go on.

That’s only 1% less than the rate of suicide while actually interned in the concentration camps. (People were committing suicide at a rate of 25,000 per 100,000 in the camps. That’s 25%. source )

Which tells me one thing: being set free doesn’t mean internal war automatically ends.

‘Survivor’ doesn’t mean the end to the struggle. Doesn’t mean the end to the pain, the heaviness, the darkness, and the cuts we have that may scab over a thousand times as they continually get picked off and bleed again until they finally heal and become scars.

Maybe we need to revise the title. Maybe we need to use the active tense like addicts in recovery do.

Maybe we are not survivors as much as we are ‘surviving.’ Maybe the work is always in process. Because I’ll speak for myself here, but I know for me, I’ll never be the same. And that doesn’t have to be a bad thing. That doesn’t have to be my whole identity. It doesn’t have to mean I don’t lead a full, beautiful, healthy life.

Survivor indicates that I did it. That it’s done. That I survived.

But just as one does not ‘survive’ grief — they grow through it, are changed by it, and they carry that change, and that loss with them — that’s how this feels.

Long after the nightmares have stopped, long after the therapy has ended, long after life has moved on and I have built a new, beautiful, healed existence, I imagine there will be times, even decades down the road, where something pricks my tear ducts and pinches the back of my throat as I once again grieve the remnant sadness that this has left in my hands.

On the other hand, though, the ‘survivor’ title indicates to me that the active fight is over.

I feel that. Finally. For the first time. I feel that in my bones. I can breathe. I can sit. I can be still, and I can actually hear the silence. I can rest my mind and my body. And my God, how they need the rest.

For that, I celebrate. In that way, I am free. I don’t have to fight anymore. All that’s left is to kneel down in the sadness, and start to do the work that it requires to grieve those losses, and to grow from here.

It’s going to take my breath away to see the beauty that I’ll make out of these ashes.

I have to trust that process.

* * * * *

To everyone who reached out to me the day of my original post, your love and kindness overwhelmed me and carried me. Like, I sat in a bathroom stall in the Sacramento Airport for longer than I’d like to admit softly sobbing as I read your words. Your words, your support bolstered me, they helped wash away my fear, my feelings of weakness, and they gave me the strength to gather my breath, to put one foot in front of the other, and to go into that room knowing that I was not alone.

I have never, in my entire life, felt more supported. Really. There is this biblical saying — ‘since we are surrounded by such a great cloud of witnesses… let us run with perseverance the race marked out for us.’

You all reached out, and it gave me this vision of this great crowd of people, of you guys, who were with me in spirit. And it made a tremendous difference.

Thank you for reaching out. Thank you for your support. Thank you for carrying me through.

* * *

If you know other people who have endured trauma, other survivors, reach out. The rules-of-thumb are the same as when someone is in grief.

Send a card. Send a note. Send a gift. Invite them to hang out with you (invites for specific plans are best — ‘Want to come play games on Tuesday night? Say 7?’; ‘Want to see this movie at 8 tonight?’). See if they want to go on a walk. Give them a gift certificate for a massage or to have their house cleaned. Send them funny things. Leave a voicemail just saying you love them. Tell them about tv shows and podcasts and books you think they might like. And, if you’re in a position where you’re able and willing, offer to be a safe listening ear if/when should they want to talk about anything.

Healing is a journey, a process, and kindness and love are what make that process a little lighter along the way.

Jo O’Hanlon is an adventurer and storyteller. She tries to be honest about the ugly and hard parts of life, and the beautiful parts too. This blog is one of the places she shares her thoughts and stories.

Other places are

instagram: @jrolicious storyofjoblog@gmail.com